The Lean Startup is a Lie

The lean startup methodology is not as successful as it is made out to be. While the framework features methods for testing hypotheses and challenging assumptions, the lack of these methods are not what is preventing failure or propelling businesses to new heights.

Originally published on medium.com

2022 Update

UBS acquires Wealthfront in January 2022 – leaving only Dropbox left from the example companies outline in the book.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: senior management realizes their company’s growth and innovation is stagnant. This realization sends shivers down their spine. Something must be done to jump-start growth.

You can test this hypothesis by looking at the number of innovation related business books published each decade. Jump on Google and quickly discover The Lean Startup positioned in the results for “best books for business innovation.”

Translated into thirty languages. A million copies sold. A vague memory of a colleague recommending the book. All the social proof necessary one might need to purchase their very own copy. Page after page the secrets behind the most successful startups spill out: minimum viable products, continuous deployment, split testing, actionable metrics, pivot, and the virtuous cycle of build, measure, learn.

The ideas are powerful, but the narrative is false. Even Mr. Ries hints at this.

“There is a myth-making industry hard at work to sell us that story, but I have come to believe that the story is false, the product of selection bias and after-the-fact rationalization. ” — Eric Ries

Seven years after the book’s publishing, Ries’ perspective on selection bias and after-the-fact rationalization rings true, only now in regards to his book. Methods and companies highlighted are victims of selection bias. The supporting qualitative evidence is shoehorned for congruity.

The Dropbox “Video MVP” is a masterful example of intentional, audience-aware viral marketing after the company spent 18 months building a reliable platform. In fact, Drew Houston used this technique twice. First to gain the attention and acceptance of Y Combinator in 2007 and again to target the Digg.com audience in 2008 prior to their public beta. It’s neither an MVP, nor a vehicle for testing a hypothesis.

Quite simply this is growth marketing.

Search Google for “Video MVP” and you will uncover zero evidence of other startups successfully deploying this technique to validate product-market fit. Additionally, most startups in the book failed the test of time. Whether their goal was to truly persevere and join the ranks of Amazon, Facebook, or Google is unknown.

A (mostly) complete list of the startups mentioned in the book:

- Dropbox, 500M users, revenue of $1B, valuation at $10B — and the only company that wasn’t following lean principles when building their product

- Food on the Table, founded by IMVU alumni, acquired by Food Network and shuttered in 2014

- Aardvark, acquired by Google and shuttered in 2011

- Groupon, IPO in 2011 and raised additional post IPO funding in 2016, was burning cash in order to fuel explosive, now hollow growth; famously crippled small businesses with bad customer traffic

- Votizen, acquired in 2013 by Causes and shuttered after 2012 election, its user database repurposed in Brigade product

- Grockit, acquired by Kaplan in 2013, its IP and users repurposed by Kaplan, while the team left to focus on the now defunct Learnist

- Zappos, acquired by Amazon in 2009 for its high culture alignment and its success in a retail category that eluded Amazon previously

In hindsight, the book’s anecdotes point toward moving quickly to the safest landing possible. Sell off valuable assets such as customer traffic, customer data, or intellectual property, and move on. There is one company in the book that exemplifies the build-measure-learn flywheel: Wealthfront.

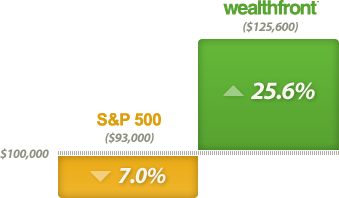

Wealthfront slowly pivoted away from simulated investing to a SaaS investment platform somewhere between 2007 and 2011. This move connected the nouveau riche of Silicon Valley to mutual fund managers claiming to beat the market by over 32% after the 2008 market crash. Wealthfront’s idea democratized a tool of the traditional neighborhood investment broker: the ability to select investment “sleeves” from top fund managers to place their clients’ funds in.

It’s hard to know when this pivot actually took place. Like several stories in the book, facts and dates don’t align with verifiable sources. A look at Wealthfront’s site from 2010 shows this product a year before the book’s timeline. By December 2011, Wealthfront moved again from the mutual fund experience to the ETF robo platform they are now known for.

This high-margin model, coupled with compounding annual returns is an ingenious idea that is seemingly glossed over. And more, the customer experience iteration, moving from requiring knowledge of good investments and investment managers to recommending a MPT portfolio echoes the product simplicity found in Dropbox. This new product simply works, reducing the barriers to entry for mass market consumers. This lesson in business fundamentals and customer experience is sadly untold.

“Every moment in business happens only once. The next Bill Gates will not build an operating system. The next Larry Page or Sergey Brin won’t make a search engine. And the next Mark Zuckerberg won’t create a social network. If you are copying these guys, you aren’t learning from them.” — Peter Thiel

The Wealthfront of 2018 is the same product from 2012, only now with a mainstream brand and val prop after years of iterations. The product team is focused on differentiated feature innovation instead of wide pivots. One recent launch is the ability to borrow against your investment. Not a new concept, however Wealthfront addressed the biggest consumer pain point when borrowing from retirement investments: the inability to participate in the market. Now the business is able to compound earnings by capturing their typical management fee, while collecting comparatively low interest on the loan. Loan revenue is up to twenty times greater than their portfolio management fee.

You know what’s better than 10x? 20x.

Wealthfront’s digital interface to algorithmic, risk-weighted ETF portfolios, was pioneered by Betterment in 2008 and available to the public by 2010. Industry leaders Vanguard and Schwab quickly reproduced the business model, launching similar products, and respectively taking the #1 and #2 positions in total managed assets in the robo advice category. Published figures show Wealthfront manages closer to 0% than they do 1% of the addressable market in terms of total assets invested via robo-advice products. Wealthfront is actively iterating against a local maximum.

“Even in engineering-driven Silicon Valley, the buzzwords of the moment call for building a “lean startup” that can “adapt” and “evolve” to an ever-changing environment. Would-be entrepreneurs are told that nothing can be known in advance: we’re supposed to listen to what customers say they want, make nothing more than a “minimum viable product,” and iterate our way to success. But leanness is a methodology, not a goal. Making small changes to things that already exist might lead you to a local maximum, but it won’t help you find the global maximum. You could build the best version of an app that lets people order toilet paper from their iPhone. But iteration without a bold plan won’t take you from 0 to 1. A company is the strangest place of all for an indefinite optimist: why should you expect your own business to succeed without a plan to make it happen? Darwinism may be a fine theory in other contexts, but in startups, intelligent design works best.” — Peter Thiel, Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

If the narrative is false, what is true? The Lean Startup succeeded in providing an update to the business lexicon used to describe entrepreneurial practices and tendencies. The concepts and frameworks are real, with repeatable methods for testing hypotheses and challenging assumptions. But are those hypotheses valuable? Ries himself warns that most startups fail. These lean methods are generally not what is preventing failure or propelling businesses to new heights. Organizational success requires much more than product validation and you certainly cannot replace hard work, good ideas, luck, and timing with someone else’s historical roadmap.

Readers of The Lean Startup must understand that the stories contained inside its pages are outliers. Find inspiration in these stories, but apply judgement to your own business problems. Start building today and avoid falling in love with myths of success. No one in the history of innovation books has duplicated past success following someone else’s playbook. Work hard and be thoughtful about your own principles. Here are some of mine:

- Care deeply about your business, craft, and customers

- Embrace experimentation and validated learning

- Develop mechanisms to break biases

- Create high-motivation environments for teams

- Collaborate with human-centered design techniques

- Don't mistake growth hacking with building an MVP

- Learn to spot outliers